In his essay,’ Academically Adrift’: the News Gets Worse and Worse, Kevin Carey, explains that there is more information that not only do college students fail to learn in college, but also that students who perform lower on the CLA (Collegiate Learning Assessment) also fail to find financial security after graduation.

In an earlier post, I discussed some of the conclusions I reached from the sections of the book which I had read. Those conclusions were:

- There is an inverse relationship between the number of faculty publications and a faculty orientation toward students.

- The higher students’ grades in the course, the more positive the student evaluations.

- Grade inflation probably exists.

In a later post, I discussed critical thinking as a concern: that students don’t “enjoy” the challenge of traditional problem solving the way I (and other faculty) do and that has an impact on whether students learn. If students do not see tackling and solving problems as a challenge (and we as educators should do as much as we can to make problem-solving interesting), then there will be a significant impact on student learning.

A Not So Radical Transformation in a Core Business Course

In the introductory business law course that is required for all business majors, all the faculty teaching the course agreed to make substantial changes in the way the course was taught in order to acknowledge and address perceived efficiencies: students lack of college-level ability to read, college-level ability to write and need to improve critical thinking. Students complained a great deal about the additional work.

Assessing and Working to Improve Reading Skills

Although my own experience with students confirms that it would help for them to have more practice reading and writing, the students did not agree. When asked whether My Reading Lab (a publisher-created product) helped them, students said no:

Note that this response is only the student’s perceptions. We have not yet completed an analysis to determine whether those who performed better on My Reading Lab performed better on the tests or in the course. We will work on analyzing that data later. This also does not included longitudinal data, i.e. would students, upon reflection, decide that they had learned more than they thought by the additional practice reading. However, what this data does show is that students did not embrace the additional reading practice and testing requirement.

Reading the Textbook

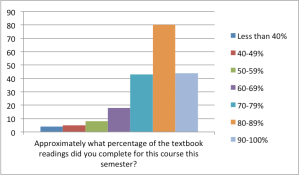

Student preparation for class is a concern. Many students do not read before attending class; they attended class then read after class. In addition, students did not study. As part of the course redesign, we required quizzes prior to students attending class. Students (74.2%) agreed that the quizzes helped them keep up with the reading. Even though the students said the quizzes helped them keep up with the reading, many still didn’t read everything. The following graph lists the students responses about whether they had read the textbook (this is at the end of the semester):

Note that 40/202 or 19.8% read 90% or more of the readings and 80/202 or 39.6% read 80-89% of the readings. That means that nearly 60% of the class read 80% or more of the readings. These are the results obtained after faculty required that students read and take a quiz on the material before attending class. Thus, students were more motivated to keep up with the reading. How would these results differ if the students had not been required to take a quiz before attending class?

Studying

Student preparation and studying. The following graph includes information on the hours that students studied.

According to these self-reports, 21.2% of students studied between 1 and 3 hours per week, 27.7% of students studied between 3 and 5 hours per week, and 21.7% of students studied between 5 and 7 hours per week. Students should have studied nearly 8 hours per week (2 hours per week outside class for each hour of class-this was a 4 unit course). In Chapter 4 of Academically Adrift, the authors note that students report spending 12 hours per week on their courses outside of class. According to figure 4.2 of the book, in a 7 day week, students spent approximately 7% of their time studying.

Conclusions so far

The educational process requires that the faculty and the student participate, and if the students have not completed their share, then education and learning wouldn’t necessarily take place. I don’t know how this data compares to other studies on student reading, but it is challenging to help learning if both parties are not fully invested. Students have a variety of reasons for that lack of involvement, but if the investment in education is relatively small, then improvement in learning will be small.

In addition, this past semester, my student course evaluations were much lower (this was also partly due to a change in the institution’s survey evaluation instrument). Because I am tenured, I do not face losing my job over the changes in my student evaluations (although adjunct faculty face a different reality when it comes to being rehired). However, adjunct faculty depend on good student evaluations in order to keep their jobs. If that is the case, adding rigor to a class could cost that faculty member his or her job.